Lean Data Analytics: High-Impact Diagnostics for Resource-Constrained Environments

Published on: Wed Jul 08 2015 by Magali Van Coppenolle

How can you build robust analytics from paper copies, ledgers and disperse spreadsheets? This is a question many leaders in fragile and developing states are confronted with.

When seeking to build their organisation, management first tries to take stock of the situation: “where are we?” and “where do we want to go?” The capacity to answer each of these questions, and push for change where needed, depends very much on the management’s knowledge of its own organisation. This, in turns, depends largely on an organisation’s capacity to generate relevant data about its own performances and capabilities.

1. What if the spreadsheet is blank?

What then, if we are faced with designing, implementing and monitoring institutional reforms in a context in which there is no data analysis to rely on with regards to an institution’s operations, functioning and performances?

This is, at first glance, the case for many organisations, including governments, operating in fragile and developing countries. For such countries and organisations, being labelled “fragile” often correlates with being labelled “data-poor”. “Data-poverty”, if accepted at face value, can have significant consequences on reform programmes.

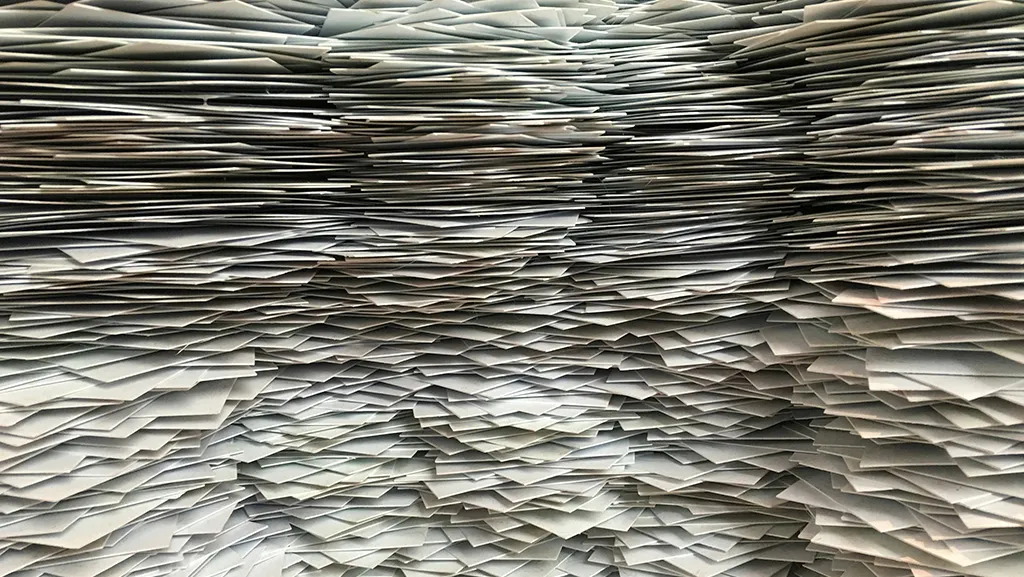

Exhibit 1: Misalignment of data-collected and data-needs

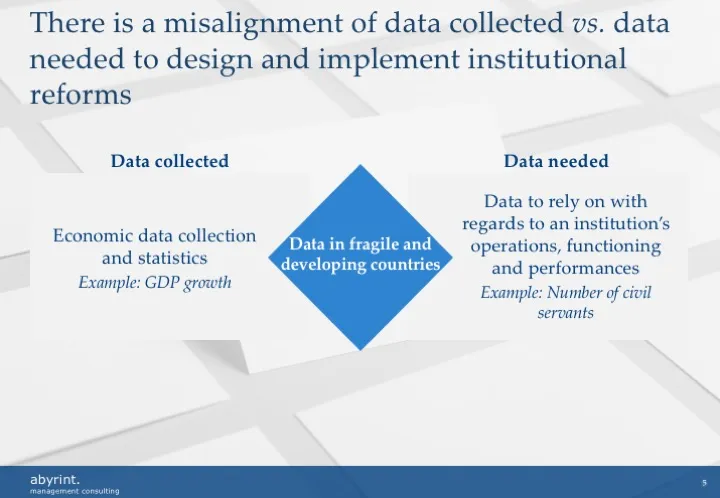

Not engaging with data analysis during initial stages of institutional reforms can dramatically increase the risk of reform failure, and this, even before any change is implemented. Among others:

- It can lead both to an under- or over-estimation of an organisation’s existing capacities and needs;

- It can lead to an issue being wrongly scoped or overlooked;

- It can result in solutions addressing issues that either: (i) do not exist, or (ii) do not have to be prioritised

Exhibit 2: Consequences of poor data analytics

Problems arising from data-poverty have been highlighted as far as macro-economic policies are concerned. There exist important programmes to develop, for example, economic data collection and statistics offices within governments in fragile countries. However, much less attention has been paid to the cause and consequences of lack of data in the case of institutional policies and reforms.

Where and how do data production processes break down and what can be done about it?

2. “Data-poor” or not looking hard enough?

Public institutions perform administrative processes that contain traditional elements of accounting, record keeping and archiving. Such activities are at the origin and core of data generation. Ledgers, payrolls or registries are goldmines of information about an institution’s capabilities and performances.

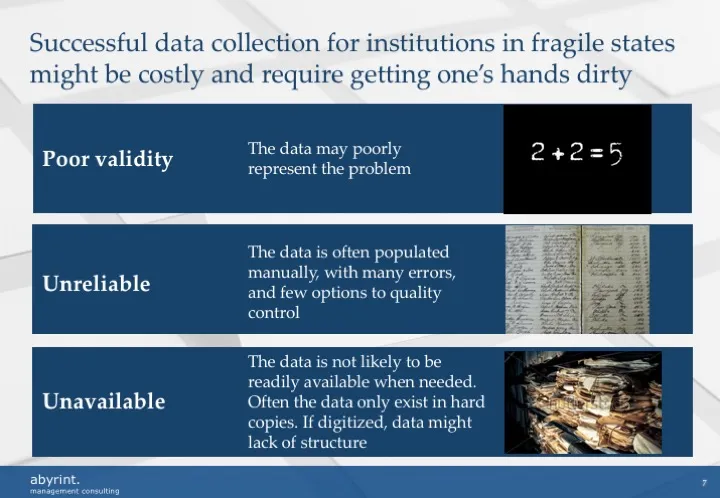

In fragile contexts, the quality of data might vary significantly and it is not likely to be readily available. Often, such data sources are populated manually and only exist in hard copies. Even if digitized, there might be a lack of structural consistency in categorization and recording practises that make the data unreliable and analysis more difficult.

These factors mostly impacts i) the time and resources necessary for data cleaning and ii) the degree of complexity of the analytics that can be performed.

There is no doubt that successful data analytics for those institutions might be costly and require getting one’s hands dirtier. But it seems that what is often referred to as “data-poverty” could be, to a certain extent, a phenomenon of not looking hard enough.

Exhibit 6: Problems of data collection in fragile and conflict affected states

‘Harvesting’, cleaning and aggregating data in institutions operating in fragile contexts can be a time- and resource-consuming process. Datasets often need to be digitised, assembled from varying sources and records are held at different institutions. Most of the times, none of those datasets were originally designed for analytical purposes. However, the price of labour is often low in fragile contexts and with some guidance, it is possible to capture critical information.

It might also be only possible to deliver analytics that are fairly simple but most often so are the questions that need answers. For example, in institutions in which the number of employees is unknown, data analytics is worth the investment prior to developing a human resource reform programme.

Moving beyond ad-hoc analytical needs, the question remains how to build sustainable practises for more fact based management.

3. Management can improve the condition by focusing on three steps:

Exhibit: Three steps to better decision making in fragile states

(1) Identify sources of information within existing institutional administrative processes. Most organisations operate basic administration processes, which include traditional elements of record keeping. Record keeping can be either a by-product of processes, such as recording transactions, or the end goal, such as building and maintaining a business registry.

Within public institutions, recurrent processes include recording information at several steps of the way. In environments in which systems and processes are not trusted by individuals, it is not unusual to see data being recorded more than necessary. Civil servants often maintain personalised records in addition to official paperwork.

Even if such data is more or less structured with varying degrees of quality and hence more or less easy to query after the fact, identifying sources of information allows for data collection and better analytics for programme-specific needs.

(2) Improve existing processes by building sustainable information management practises. The main objective is then to streamline how information is collected and made available for analysis.

Much can be done with minimum technology means. It is possible to nudge record keeping offices and accounting functions in the direction of digitising and recording their information in electronic formats. In many cases, digitisation can also start as a shadow process of a manual one. The simplicity of questions to be answered, together with limited data availability, means that even analytics performed in a low-tech way are sufficient to provide critical insight into the organisation’s capabilities and performances.

It is however often useful to consider to leapfrog and do it differently. It is possible to use the potentials unlocked by decreasing cost of data collection and storage. To a certain extent, this already happens organically, as we see entire ministry’s communication stored on cloud services from regular providers. Find motivated staff that has an interest and talent in such area, they can demonstrate amazing effective and creative potential.

In terms of software, most off-the-shelf software offer sufficient services and they are cheaply or freely available. It can often be cheaper and more effective to build your organisation around a standard IT system, than to build a customised system. There are also more pitfalls in building the latter.

(3) Move from blank spreadsheets to management-by-spreadsheets. There is at times no connection or relationship between clerks recording data and their management teams. Management can be unaware of the value of existing sources of information or unsure as to how to make use of it.

An important opportunity lies in establishing a shared understanding of the value of data for management purposes and to start organising collection and recording around core information management principles. Processes of decision-making can be modified and nudged in making more systematic use of data. This also means that leadership must require management reports and regular updates of core information, thereby stimulating interest for information and data across the organisation.

In fine, with regards to institutional reforms in fragile contexts, forgoing the investment of data collection and analysis means that we do not know where we are and even less what to do about it. It is though possible to reduce the long-term high cost of reform failure for all parties. Accepting that the processes of collecting, including consolidation and cleaning, storing and analysing data are not perfect is a first step. From there, it is possible to get simple but crucially insightful analytics. This contributes to better decision-making, for external partners and programme managers among others, but most importantly for institutions undergoing reforms.

Magali Caroline Van Coppenolle is Senior Associate with Abyrint. Ivar Strand, founding partner at Abyrint, also contributed to this article.